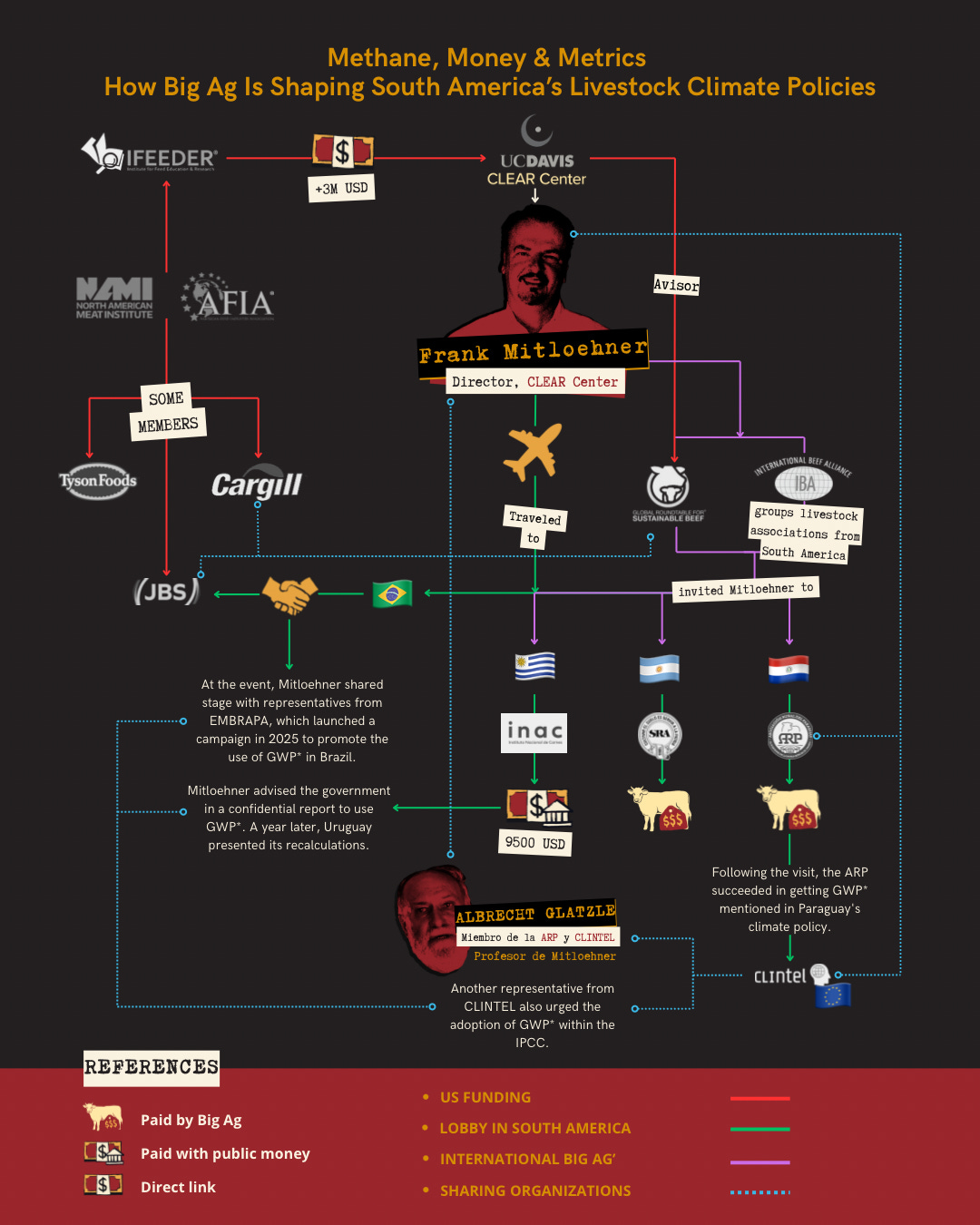

Methane, Money & Metrics: Inside Big Ag’s plan to hide its climate impact in South America 🐮🔥

Exclusive: Through figures like Frank Mitloehner, the livestock industry is pushing to change how its methane emissions are measured in Paraguay, Uruguay, Argentina, and Brazil.

If you only have a few minutes:

New research reveals a coordinated plan by agribusiness to influence climate policies in Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Argentina. The goal: to change how the impact of livestock farming is calculated.

Through a new way of measuring methane impact, called GWP*, large livestock companies could increase their pollution while claiming to contribute to mitigating climate change.

One of the main drivers of this change, Frank Mitloehner, received nearly $3 million through his research center from a foundation linked to JBS, Cargill, and Tyson Foods, among others. The goal: to “rethink methane.”

He also received $9,500 in public funds from Uruguay to advise the Ministry of the Environment and the Ministry of Agriculture during the Lacalle Pou administration. There, he recommended modifying how the impact of livestock farming is calculated.

Mitloehner also traveled to Paraguay, where he gave a talk in favor of adopting this new metric, with the support of the main livestock association of the country, who then managed to include it in the country's official policy.

Exclusive documents, photos and videos show how since 2022 Frank Mitloehner, a researcher at the Clarity and Leadership for Environmental Awareness and Research (CLEAR) Center, funded by IFEEDER, an organization linked to JBS, Cargill and Tyson Foods, traveled through Paraguay, Uruguay, Argentina and Brazil with the goal of pushing for a new way to measure methane - the main greenhouse gas related to livestock farming.

With the exception of Brazil, in the remaining three countries it was confirmed that Mitloehner's participation was supported by livestock unions related to the so-called Global Roundtable for Sustainable Meat, a global organization that includes IFEEDER contributors, business representatives from the world's largest meat producers and multinationals such as ADM, McDonald's and Burger King.

By means of an “accounting trick”, this new metric, called GWP*, would allow the livestock industry to have a free pass. Several scientists warn that, if this new way of calculating methane is adopted, countries and multinationals will be able to dodge their undeniable responsibility for climate change.

In the most extreme case, this new metric would also allow them to claim that they are offsetting emissions from other sectors, such as fossil fuels, and receive benefits in the form of carbon credits as a result.

All without changing their unsustainable production model and while they continue to warm the planet, jeopardizing the objectives of the Paris Agreement.

That is why the GWP* metric has already been rejected by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the body that guides the science for climate policy.

In Uruguay, contracts accessed exclusively show that Mitloehner received $9,500 dollars of public money to advise the Lacalle Pou government on climate policies related to agriculture and the adoption of this new metric, including meetings with his ministers of environment and agriculture at government headquarters.

And in Paraguay, exclusive internal documents show that following his visit, representatives of the Paraguay Rural Association successfully pushed for the country to consider the use of GWP* in its official climate policy.

In addition, Mitloehner confirmed that he traveled at the expense of Argentina's Rural Society in order to spread what he calls “the real methane story” at events in that country. In Brazil he did the same at a forum promoted by JBS, the world's largest meat company. Also in Brazil, Myles Allen, one of the creators of this measurement, promoted at an event that agribusiness representatives lobby their governments to adopt this new way of calculating methane at the next COP30 in Bélem.

Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay and Brazil will jointly negotiate agricultural issues at the climate conference.

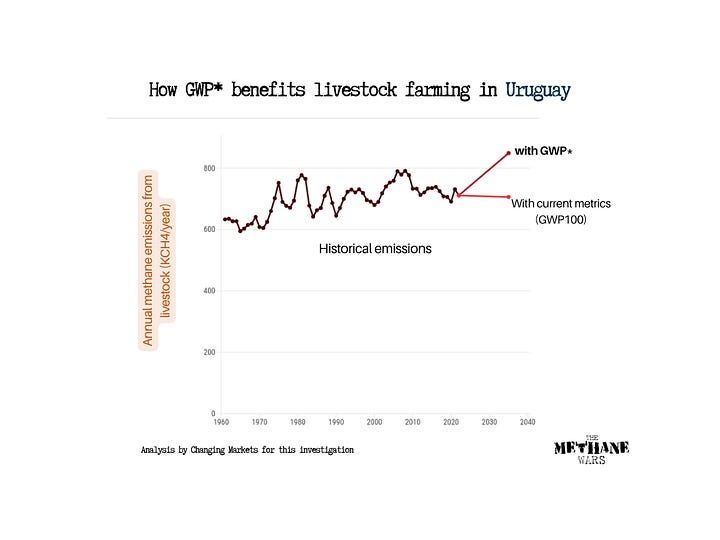

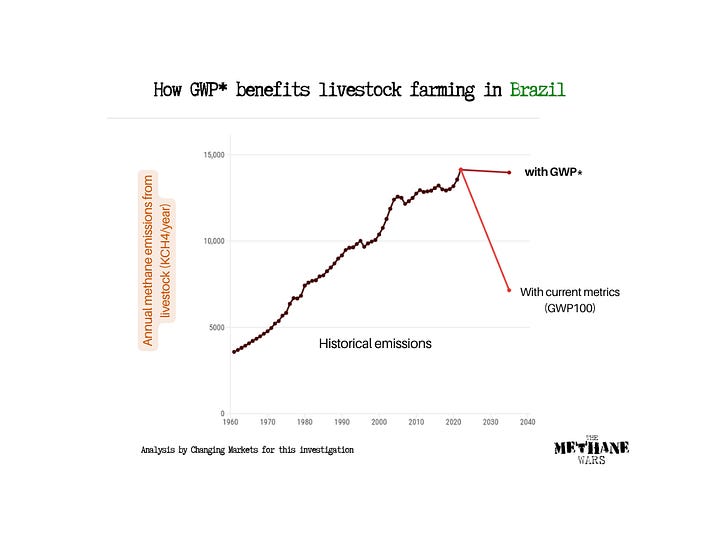

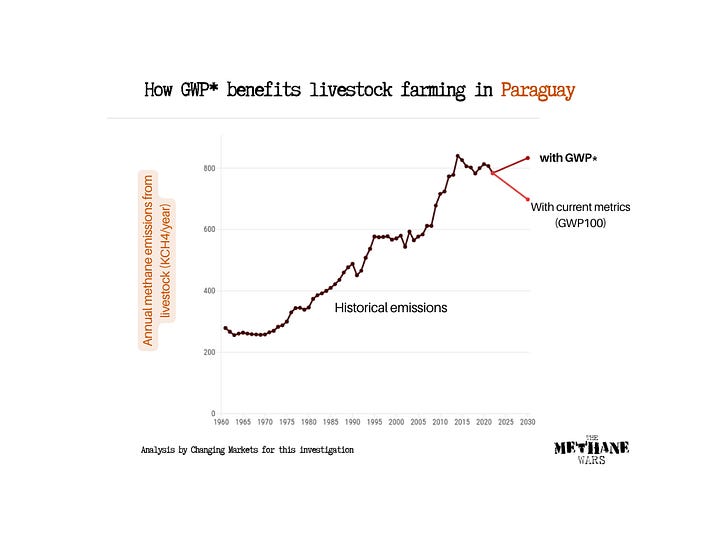

An analysis conducted for this research shows that the adoption of GWP* would allow livestock farming in the four countries to reduce their ambition or even increase their methane emissions while claiming to be in line with their governments' climate commitments.

Mitloehner's influence in South America is in addition to similar work he has been doing for years in support of livestock in countries such as the United States, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand. The livestock unions of these countries and those of South America are linked through the Global Roundtable for Sustainable Beef and the International Beef Alliance.

Fast and Furious

Every time a cow eats something, it ruminates it in its stomach where microbes ferment that food. This process serves to absorb nutrients, but also produces a gas, methane. Like any living being satisfied with its food, the cow burps, releasing methane through its mouth.

Nearly 300 million cows belch millions of tons of methane between Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay. To accommodate the vast number of cows destined for European, Chinese, or North American consumption, millions of hectares of two key ecosystems in South America had to be burned and deforested: the Amazon and the Chaco.

But while efforts are being made to curb deforestation through ever-tightening regulations from governments and markets, methane belching is the real Achilles heel of the South American and global livestock industry. In fact, agriculture and livestock are the world's largest producers of the methane that causes climate change.

Methane is fast and furious. It lasts about 12 years in the atmosphere, where it traps heat on the planet about 80 times more effectively than carbon dioxide.

We do not see it or smell it, but it collaborates in modifying rainfall and temperature patterns in the medium and long term. It is the same climate change that is making floods such as the one in Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil in 2024, or extended heat waves such as those experienced in Argentina and Paraguay in 2023, worse and more likely.

According to the IPCC, even by reducing all fossil fuel burning, if we do not change the way we produce and consume food we will cross the temperature increase threshold stated in the Paris Agreement.

That is why the IPCC concludes that rapid methane reductions are indispensable not only to meet the agreement's commitments, but to avoid breaching planetary boundaries and the loss of up to 15% of smallholder crops.

Proposed solutions to the methane problem vary. There are special feeds to improve cow digestion, projects to optimize productivity per hectare and calls for - especially in developed countries - diversifying their diets and consuming less meat.

The livestock industry is opposed to this.

That's where a man named Frank Mitloehner comes in. A recurrent speaker at forums, meetings with ministers, specialized media and statements in parliaments. In conjunction with the organization he leads, the CLEAR Center at the University of Davis in California, he proposes that in the face of the methane dilemma, what we must do is simple: change how it is calculated.

To that end, he is promoting a new metric called the Global Warming Potential Star (GWP*), which he claims better reflects the relationship of methane from livestock to climate change.

Behind what may appear to be an obscure technical dispute lies a major political influence campaign, financed with nearly $3 million dollars from Big Ag through multinational corporations such as Cargill, Tyson Foods and JBS.

💵Big Ag’s millions in funding behind a “guru”.

In 2019, a group of scientists attempted to answer a critical question:

How do we feed 10 billion people in a healthy way, while respecting the limits of the planet?

The answer was the EAT-Lancet report. Its conclusion: it is possible.

But we must transform our eating habits. More vegetables and grains, less sugar and, especially in countries like the United States, eating less meat.

The report, which sought to guide food policies for the next decade, found instead “a digital countermovement” in favor of livestock.

It was not spontaneous opposition, but a coordinated effort that included Frank Mitloehner, a self-described “greenhouse gas emissions guru” through his newly created CLEAR Center within the University of California at Davis, US.

An investigation by Unearthed revealed CLEAR Center reports to its agribusiness donor, crediting Mitloehner for initiating “a massive campaign” that “was successful in convincing audiences to turn away from the EAT-Lancet report.”

The donor to whom the CLEAR Center reported this success was IFEEDER, the “educational” organization of the American Feed Industry Association (AFIA), which represents 650 companies directly or indirectly related to the livestock industry. Among those companies are major international agribusiness producers such as Cargill, Tyson Foods and Pilgrim's, which is owned by Brazilian giant JBS.

Other international agribusiness donors to IFEEDER include Alltech, ADM and Bayer.

According to a memo obtained by Unearthed, the CLEAR Center was created following an agreement between Mitloehner, UC Davis and IFEEDER at meetings in 2018.

For agribusiness, funding Mitloehner through the CLEAR Center aligned with the goal of “sharing the message of animal agriculture's role as a solution provider in efforts to deal with climate change issues.”

According to a memo from the American Feed Industry Association, the content produced by the CLEAR Center was useful in influencing “public policy discussions happening internationally and nationally, changing the future of the industry.”

Above all, the support was because “Mitloehner provides a neutral, credible, non-industry voice for journalists and stakeholders at conferences and other important government activities.”

According to Unearthed, the CLEAR Center also received funding from Burger King following a similar lobbying campaign on advertising by the fast food chain.

As stated in estimates with available documents, Mitloehner and the CLEAR Center received between 2018 and 2023 nearly $3 million dollars in direct funding from the international livestock industry.

In his entire career, including public funds related to agriculture, Desmog estimated that Mitloehner received more than $12 million dollars.

In exchange for the generous funding, agribusiness representatives such as Cargill, AFIA and the North American Meat Institute (NAMI) became part of CLEAR's “recommendations committee.” Much of the money from IFEEDER to Mitloehner and the CLEAR Center was given under a specific project: a campaign to “rethink methane”.

Backed by money from the livestock industry, the campaign to “rethink methane” soon became the banner for influencing governments around the world. The National Cattlemen's Beef Association (NCBA), which represents more than 175,000 U.S. cattle producers admitted after COP26 its lobbying efforts in Congress for the adoption of GWP*. NCBA's executive board includes McDonald's, Cargill, Tyson Foods and JBS.

It is also a member of the Global Roundtable for Sustainable Meat and the International Beef Alliance, which brings together the main livestock lobbies, including those of Ireland, Australia and New Zealand. Also those from South America, such as Paraguay, Uruguay, Argentina and Brazil. Mitloehner was invited to speak on behalf of GWP* in each of those countries, often funded by agribusiness itself. Or in the case of Uruguay, with public money.

🌍How a discussion about maths puts us in danger or worsened heat waves and floods

On June 2, 2022, in an event hall of the Sheraton Hotel in Asunción, Paraguay's capital, Mitloehner took the stage with an audience of just under 200 people. Among the participants were leaders of the country's main livestock associations and government representatives.

For almost the entire 45 minutes of what was billed as “a keynote talk” on livestock “as part of the solution to climate change,” Mitloehner focused on the need to “reclaim the methane narrative.”

He argued that methane is “the Achilles heel of animal agriculture today” because “all the people who don't like you very much, the people who don't like animal agriculture, always focus on the topic because they see it as the biggest vulnerability.”

Mitloehner explained that under the current way that all countries use to calculate the impact they produce, methane is considered “carbon dioxide on steroids.”

“This does not capture the true nature of methane,” he asserted.

To that end, he introduced attendees to a new way of calculating the impact of livestock: the GWP* metric.

The current way of calculating methane has limitations. It does not accurately take into account the fact that methane is very warming but short-lived. So, it overestimates its long-term impact on the planet. It also underestimates the short-term impact - something Mitloehner notably omitted in his presentation or when asked about it for this story.

The so-called Global Warming Potential* (GWP star) came in theory to solve the problem. This metric was not created by Mitloehner, who is not a climate scientist, but by a team led by Dr. Michelle Cain and Professor Myles Allen of Oxford University.

This new method for calculating the effect of methane on climate change estimates its contribution to global warming based on how emissions are changing according to a base year.

According to its creators, the new method better reflects the short lifetime of methane in the atmosphere.

But there are several scientists who warn about the danger of adopting GWP*, its potential for greenwashing, the incentives to favor livestock farming and even the possible derailment of the objectives of limiting the temperature increase set by the Paris Agreement.

This happens because, instead of looking at the total amount of methane being sent into the atmosphere, the metric focuses on seeing that it is not “additional warming,” which would allow governments and companies to continue steadily emitting large amounts of methane, rather than reducing it.

An accounting trick that, as the Changing Markets' “Seeing Stars” report explains, considers that past emissions are not relevant because they are “constantly being recycled”.

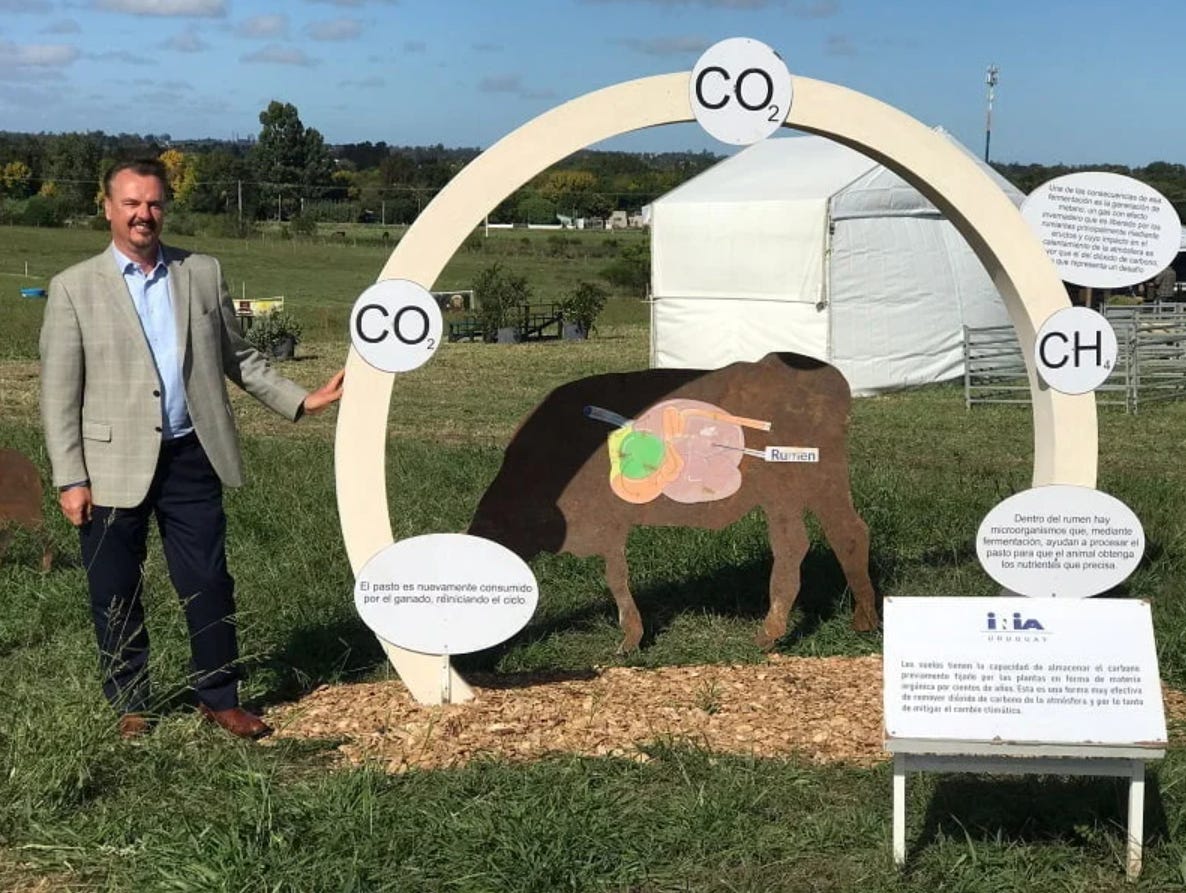

It is the refined version of another old narrative used by agribusiness when questioned about its impact on climate change. One that describes a perfect world in which methane belched by cows is recycled by pastures through photosynthesis.

What this narrative ignores is that even during its short lifespan in the atmosphere, methane is warming the planet and damaging air quality. And that even when it dissipates into the sky, the warming it causes lasts longer, as the heat penetrates the ocean, which can take decades or centuries to warm or cool, contributing to sea level rise and putting the planet at risk of flooding, more frequent hurricanes and profound damage to biodiversity.

It also assumes that in the time period of this cycle there will be neither alterations in the number of livestock, nor frosts or fires that affect pastures and soil.

Mitloehner in front of a cutout illustrating the “perfect cycle” of methane from livestock farming in Uruguay, 2022. Photo: INIA, Uruguayan Govt.

“Methane is not perfectly recycled,” says Nicholas Carter, a food systems and disinformation researcher and one of the authors of “Seeing Stars”. “What happens is that the complexity of the issue is functional to the livestock industry, because much of the scientific communication on climate has focused on carbon dioxide and not how methane works,” he points out.

In the words of the IPCC, the GWP* “does not capture the contribution to warming that each methane emission makes”. That is why the international body rejected its adoption as a metric in its latest scientific report.

Under this new metric, a country like New Zealand can continue to have millions of cows belching out thousands of tons of methane. As long as that number of cows is stable, the GWP* will consider that it is not “additional warming” since under the calculation, it is methane that will be destroyed at the same rate as it is emitted.

One of the scientists who created the metric, Dr. Cain, wrote that under her new way of calculating methane in New Zealand all other sectors would get “a free pass (...), courtesy of the farmers.”

A free pass that the New Zealand government is considering. In 2025, climate scientists warned in a letter to New Zealand Prime Minister Christopher Luxon that the adoption of GWP* aligned targets “ignore the scientific evidence” of methane's impact.

In a presentation in May 2025 in Australia, Mitloehner considered the New Zealand government's intention as “a smart move”. Something he defended again when consulted for this research.

When asked about his concerns surrounding the metrics, Matthew Hayek, assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Studies at New York University and one of the signatories of the letter to the New Zealand government, stated that “different language and metrics are being used by a number of countries to delay progress in reducing methane.”

For Hayek, “this includes countries considering adopting GWP*, which can incorrectly make it appear that a country is cooling the atmosphere even as global methane emissions continue to grow and warm the planet.”

For the expert, one of the risks is that "some of these countries are seeking to use this supposed cooling to offset their contributions (to climate change) in other sectors. But just reducing a country's methane emissions cannot “compensate” for fossil fuel emissions; this is impossible.

An illustrative analogy was given to the Financial Times by Paul Behrens, professor of environmental change at Oxford University: "It's like saying if I'm dumping 100 barrels of pollution into this river, it's killing life. And then I dump only 90 barrels, then I should be rewarded for it."

This idea was advocated by Mitloehner himself in an interview in 2023, where he argued that “the (livestock) industry could offset all the global warming contributions of our sector, some of the historical emissions and some of the carbon dioxide from the fossil fuel industry”. Also by authors of the metric in a 2019 report.

Asked about the IPCC's position via email, Mitloehner admitted that “they had a point” and that “even if we manage to keep methane emissions stable, something known as climate neutrality, these emissions will continue to drive historical warming.”.

However, he stated that “climate neutrality in agriculture would be an achievement, as it would be the result of a significant reduction in methane emissions”. Mitloehner's full response can be found here.

But the data show otherwise.

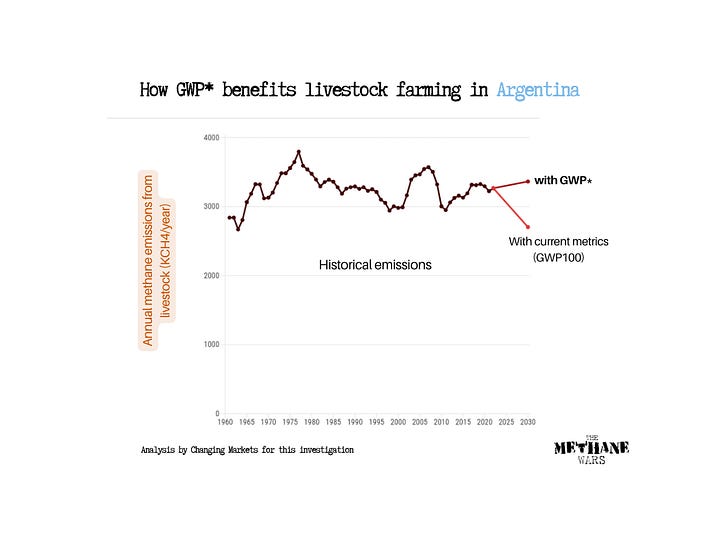

An analysis of Changing Markets for this research shows that by applying GWP* the livestock sector in Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay could continue to increase their methane emissions while claiming to be in line with their countries' climate commitments.

Under current metrics, meeting the same commitment requires the sector to rapidly and decisively reduce the contribution of livestock production in these countries for climate change.

In the case of Brazil, applying the GWP* metric will require the livestock sector to continue to reduce methane from its cows but at a much less ambitious pace than the new commitment the country made in 2024.

For Caitlin Smith, senior specialist at Changing Markets, the objective is clear: “Promoting the use of GWP* at a regional or sectoral level is another tactic by agribusiness to distract us from their significant methane emissions and avoid action to reduce them”.

"It is a new scientific trick to claim that their production does not increase global warming. And that with small reductions they can claim carbon neutrality", says Alma Castrejón-Davila, a researcher at the same organization.

This analysis sheds light on why agribusiness in the four countries is interested in Mitloehner's work. An interest that, in the case of Paraguay and Uruguay, has already translated into influence on official climate policies.

Mitloehner's links to agribusiness in Paraguay, Uruguay, Argentina and Brazil

Frank Mitloehner confirmed that his presence in Paraguay was because of the invitation of the local chapter of the Global Roundtable for Sustainable Meat, which includes everything from the Ministry of Agriculture of that country to McDonalds. The North American researcher confirmed that the trip was paid for by the Mesa de Carne Sostenible.

The objective of the Mesa in Paraguay is to “promote the sustainability of the Paraguayan beef value chain”. But its president in 2022 was Alfred Fast, a representative of the Paraguayan Chaco cattle cooperatives and a skeptic of the impact of human activities on climate change.

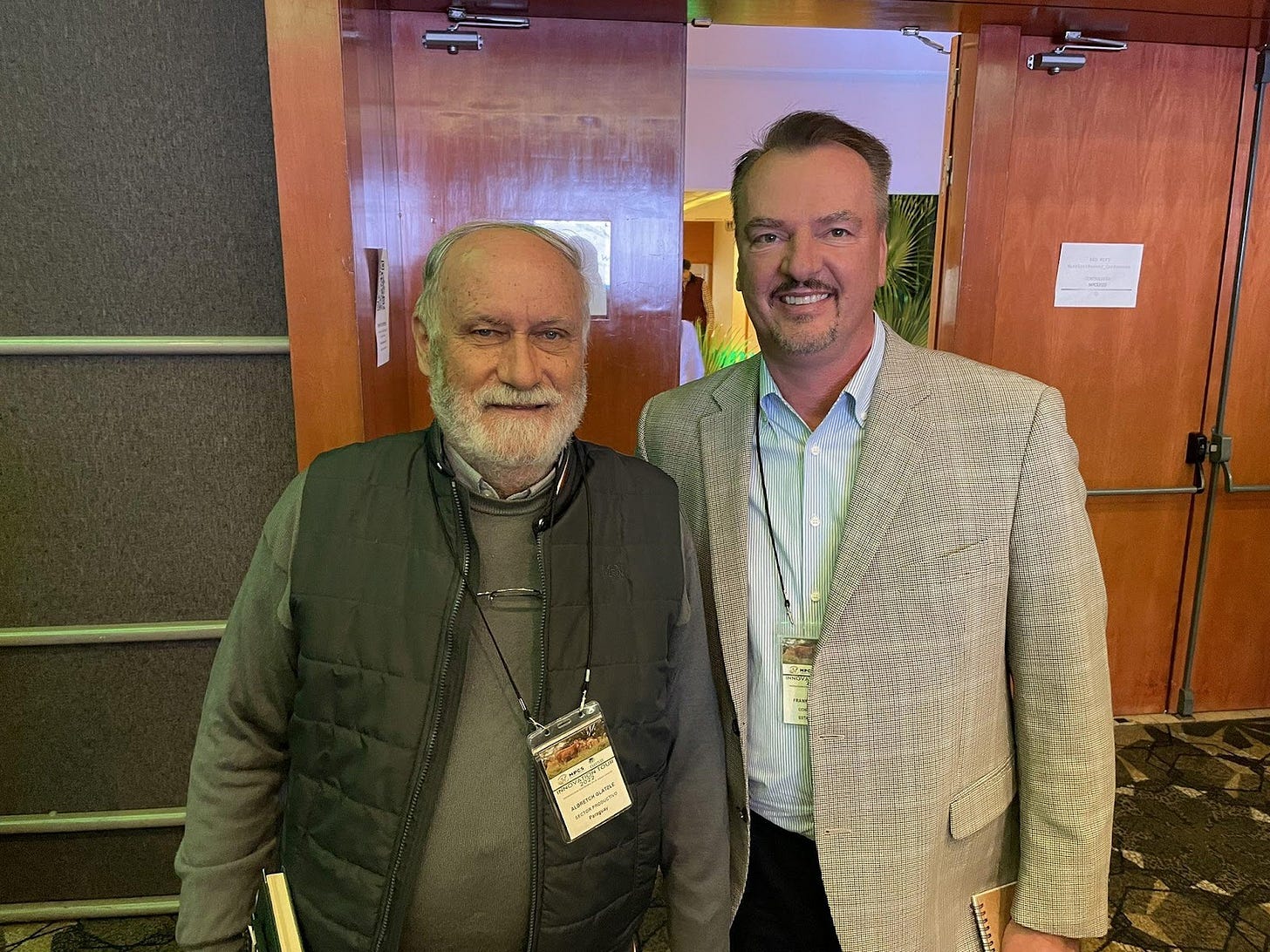

Also at the event were two representatives of Paraguay's National Climate Change Commission, the deliberative body that must approve the country's climate change policies. One was an old friend of Mitloehner's, Albrecht Glatzle.

Frank Mitloehner and the representative of the Paraguayan Rural Association to the National Climate Change Commission, Albrecht Glatzle, after the event in June 2022. Photo: X profile of Frank Mitloehner.

The two have known each other for more than 30 years, when Mitloehner was just a student visiting the Paraguayan Chaco and Glatzle was his supervisor. Now, Glatzle was in charge of defending the interests of the powerful Paraguayan Rural Association, the country's main livestock association, in the Climate Change Commission. Glatzle is a known climate change denier, something Mitloehner, in his defense, says he does not share.

Glatzle is a contributor to CLINTEL, a European denialist organization founded by a former Shell employee. Another CLINTEL member, Irishman Jim O'Brien, was the one who had proposed to the IPCC to adopt GWP* as a metric for calculating methane from livestock.

The other member of the National Climate Change Commission present was Norman Breuer (+), an agricultural engineer and livestock project consultant. Breuer was already familiar with Mitloehner's work and shared his drive to change how livestock methane was calculated.

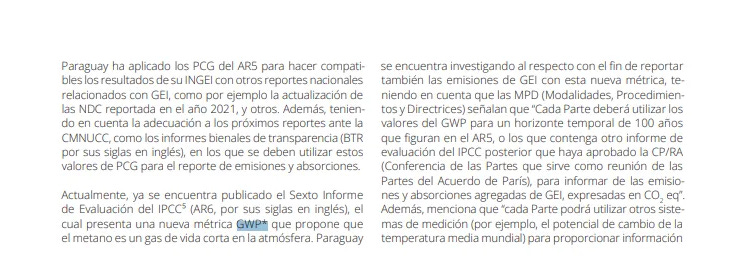

In September 2022, after the event with Mitloehner and with the support of the Rural Association of Paraguay, Breuer managed to get mentions of GWP* included in the update of its climate policy that the country submitted to the United Nations in 2023. This is evidenced by exclusive internal documents from meetings of Paraguay's National Climate Change Commission.

Breuer's recommendation was not innocuous.

This was after technicians from the Ministry of the Environment informed representatives of the Commission that, after recalculating Paraguay's emissions, agriculture and livestock emitted almost twice as much greenhouse gas as previously reported. This was largely due to methane from cow belching.

In December of the same year, during the climate negotiations in Dubai, the government of Paraguay made an open defense of the livestock industry by officially protesting against the inclusion of methane reduction targets in the final COP28 agreement.

When asked for comment for this report, the Paraguayan Ministry of Environment stated in a written response that it was “aware” of the concerns raised about the metric, but reaffirmed that Paraguay “has the option of using other measurement systems” to report its emissions “additionally.” The full response can be found here.

Mitloehner not only influenced Paraguayan climate policy. He exerted similar influence in Uruguay.

Contracts accessed through public information requests show that between 2021 and 2022, Mitloehner received $9,500 dollars from the Uruguayan state through the National Meat Institute (INAC), the public body that aims to promote the country's livestock.

The payments included visits to various places in Uruguay, including the annual event of the Rural Society, the country's most powerful cattle-raising union. It also included a meeting at the Executive Tower - headquarters of the Uruguayan government - with the Ministers of Environment and Agriculture of Luis Lacalle Pou's government: Adrián Peña and Fernando Mattos. There he used the same presentation used in Paraguay.

Frank Mitloehner's presentation at the Executive Tower of the government of Uruguay in May 2022. Then Minister of Environment, Adrian Peña (first left) and then Minister of Agriculture, Fernando Mattos (next to Mitloehner) can be seen. Photo: X profile of Frank Mitloehner.

Mitloehner also received public money in reimbursement for travel costs and for drafting a guidance report for Uruguay's foreign climate policy in the framework of the COP27 negotiations in Egypt.

Although the full report submitted to the Uruguayan government was classified as partially confidential, INAC did share a summary of Mitloehner's main recommendations: “Perform livestock emissions calculations using GWP*”.

The Uruguayan government has been consulted on the scope of the implementation of the Mitloehner report recommendations since then, with no response so far.

However, in 2024 the National Institute for Agricultural Research, another public entity formed by the Ministry of Agriculture with participation from the livestock sector, made a presentation promoting the use of GWP* to recalculate the impact of Uruguayan livestock farming at an international congress event organized by INAC in Punta del Este, Uruguay.

In the event where the Uruguayan entity promoted the use of GWP*, the Minister of Primary Industries of New Zealand, Petter Ettema, was also a speaker.

Also participating in the congress were the then Minister of Agriculture of Uruguay, Fernando Mattos, the Minister of Agriculture of Paraguay, Carlos Giménez, the Minister of Agriculture of Brazil, Carlos Fávaro, and the Secretary of Agriculture of Argentina, Sergio Araeta.

The Rural Society of that country invited Mitloehner to be a speaker at an event which was also attended by the now Minister of Security of Javier Milei, Patricia Bullrich, and the head of government in the city of Buenos Aires, Jorge Macri. When asked about this, Mitloehner confirmed that his trip to Argentina was financed by the cattle union.

But his most far-reaching presence was at the Methane in Agriculture Forum in Sao Paulo, Brazil, in May 2022. There he and Eduardo Assad, a former researcher at the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA), a Brazilian government agency, discussed the need to adopt GWP*.

In 2023, researchers from Brazil's EMBRAPA signed, along with researchers from Uruguay's Ministry of Livestock and Argentina's Meat Institute, Frank Mitloehner and Michelle MCain, one of the creators of the metric, an FAO report presented in Italy that analyzed GWP* as one of the possible metrics for measuring methane. In 2024, the agency was also present at the event where the Uruguayan government presented its recalculations using the metric.

In April 2025, EMBRAPA's Beef Intelligence Center launched a social media campaign in favor of adopting GWP*, in order to “demystify” the impact of the cattle sector.

In 2024, during a forum organized by the state government of Sao Paulo in Brazil, Myles Allen, the Oxford scientist who created the metric, asked attendees to “convince their governments” to have the GWP* adopted at the COP30 climate negotiations in Bethlehem as the new way to measure methane.

There is no evidence so far that, unlike Paraguay and Uruguay, the governments of Argentina or Brazil are considering adopting the use of GWP*,

Nevertheless, the signs of adoption of GWP* in Uruguay and Paraguay generate a risk of a domino effect in the agriculture negotiating group of which Argentina and Brazil will be part at COP30 in Belem in November 2025.

The interest in promoting GWP* is not only from governments. Mitloehner was a speaker at an event organized by none other than the largest meat company in the world: JBS. When asked about it, Mitloehner denied that his presence in Brazil had been paid for by JBS, arguing that his trip was “for personal reasons”.

According to a 2024 report by the European organization FoodRise, GWP* “would be a free pass or actively benefit a multinational livestock company like JBS, which is estimated to pollute at the same level as Spain”.

On the contrary, the report notes, adoption of the metric “would severely punish small livestock producers in the Global South”.

This is admitted by a study signed by Mitloehner himself, which shows that using the new methane calculations, Brazilian livestock farming would be in a place of greater historical responsibility for climate change than it is today.

JBS was consulted about its ties with Mitloehner and its position on the adoption of the GWP* metric, with no response so far.

Although Mitloehner denied that JBS directly funded him, its North American subsidiary, Pilgrim's, is part of the American Feed Industry Association (AFIA), which according to documents provided Mitloehner and his research center with millions of dollars in its campaign to “rethink methane.”

“To achieve effective climate action, it is essential that methane receives the attention it deserves. Given that one of its main sources is the livestock sector, any change in the way its emissions are measured must be carefully evaluated,” says Camila Mercure, public policy specialist on climate change at the Environment and Natural Resources Foundation (FARN – Argentina).

For Professor Hayek of New York University, «multiple scientific articles have already concluded that GWP* is not a safeguard or a way to justify the unjustifiable. Some of the countries that are considering it are already among the largest emitters of methane in the world».

The changes promoted to methane metrics are not the only way in which agribusiness seeks to free itself from its responsibility for climate change.

In the next installments of this series, we will see how the sector seeks to position itself with questionable proposals.

Frank Mitloehner (second right) at the JBS event on methane in agriculture in Brazil, May 2022. Source: JBS

Investigation: Maximiliano Manzoni, Bertha Fellow 2025

Editors: Francisco Parra & Paula Díaz, Climate Tracker LATAM

Ilustrations: Enrique Bernardou & Wylliam Matsumoto

Photography: Nicolás Granada

This piece was produced as part of the Bertha Challenge Fellowship